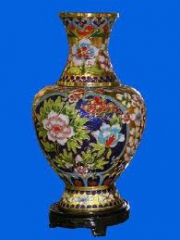

Cloisonne Appraisal

The French named it and the Chinese do it; well maybe not exclusively, but the many small factories at least in Beijing attest to the Chinese influence in a form of enameling called Cloisonné. I recently visited one of those small artisan’s shops to observe firsthand and up close the entire process beginning with sheets of raw copper on up to richly adorned, multi-colored porcelain Cloisonné vases and other items..

The French named it and the Chinese do it; well maybe not exclusively, but the many small factories at least in Beijing attest to the Chinese influence in a form of enameling called Cloisonné. I recently visited one of those small artisan’s shops to observe firsthand and up close the entire process beginning with sheets of raw copper on up to richly adorned, multi-colored porcelain Cloisonné vases and other items..

Although I saw the process in fast forward steps, the reality is that each piece, whether it a vase, a figural statue, or a floral arrangement requires thirty-three handcrafted steps to completion spread over as much as forty days labor. Cloisonné, she explained to me, means separation or partitioning of colored areas by thin metal strips.

It seemed simple enough by her description but, as I was soon to learn, very complex in nature. The first phase begins with a copper sheet cut into five separate pieces; each to become a section of a vase, as an example. Imagine the visual components of that vase beginning at the top rim or mouth; the narrow neck; the shoulder as the middle begins to bulge out; the fat part or the stomach, and finally the bottom. These anatomical descriptions came by courtesy of my Chinese guide who felt that this touring American might better understand the details in simplified fashion.

Next a technique is used that is hundreds of years old. The pure copper sheets are repeatedly heated and hammered into the various parts of the vase, bowl, pot or other desired shape. The copper is smelted in a coal-lined hole. If copper is cold it can be easily split with a hammer. An open forge can heat the copper to over 2,000 degrees. By using two horizontal bellows a draft of air intensifies the fire. As the copper is repeatedly heated it becomes malleable and is shaped by hand with hammers. By first forming a bucket, the copper can be formed into any desired object. The pieces of copper are then tig welded together, which involves the use of Tungsten gas and filler rods to join the pieces of metal together. This multi-step phase consumes two days of the process.

The second phase requires a steady hand and tireless eyesight; a job best suited to women, my female guide smilingly assured me. Tiny strips of metal, usually copper, are bent, formed, and applied to the rough surface of the vase using vegetable glue to form the decorations. The copper strips are about 1/16 inch thick and as long as the artist needs. The decoration phase is not entirely by happen-chance. The artist has an idea or ‘blue print’ of the pattern in mind when the work begins and will make full use of her experience, imagination and creativeness when setting the copper strips onto the body. This arduous task takes five days for each item.

The third and final phase involves the enameling. Enameling is the process of applying a specially prepared glass to a copper sheet and fusing the two together through the use of intense heat. The colored ground glass in this shop was applied by hand. After the colors have been applied to the copper, the enamel is then fired in an electric kiln where the glass melts and adheres to the copper. This process may be repeated up to 20 times until a painting is finally completed.

Keep in mind when you next see that beautifully decorated an expensive oriental vase on a dealer’s shelf, enamel is a unique medium in regard to its quality. It is regarded as an eternal medium, where the colors do not fade with time and its texture remains true to form. Another unique characteristic of enamel is the brilliance and richness of color that is unsurpassed. From the many layers of applied colored glass ascends a lustrous depth that creates strong, beautiful hues of saturated, rich color.